This article was originally published by the Shannon Point Marine Center at Western Washington University.

Circulating between the Marrowstone Marine Field Station, Shannon Point Marine Center, and a home base/impromptu animal shelter on Whidbey Island, researcher Dr. Chris Murray embodies the can-do attitude that buoys many successful marine scientists.

Chris arrived at Shannon Point in September 2019 as a visiting scientist in search of a regional facility in which to conduct ocean acidification research. Having received a post-doctoral fellowship with the Washington Ocean Acidification Center, he wanted to build on his doctoral research into Atlantic sand lance (Ammodytes dubius)1 by conducting a comparative study on the Pacific species (Ammodytes hexapterus).

Shannon Point’s experimental ocean acidification facility turned out to be just the ticket for this study design. Chris is particularly interested in how multiple stressors, acting in concert, affect these ‘forage fish’ that are key prey species for commercial fish species, marine birds, and mammals. Rarely does a single stressor, such as ocean acidification alone, affect a marine species. The anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions that give rise to ocean acidification are also closely related to marine heat waves, and the resulting changes in ocean circulation and productivity can also lead to low dissolved oxygen. Chris has chosen to focus his experimental research on the combined effects of elevated CO2 and temperature.

As often happens in life, events did not unfold according to plan. Pacific sand lance turn out to be reluctant experimental subjects, difficult to collect and unwilling to spawn in the laboratory, at least in winter. A lateral move to the study of Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), another important forage fish species with endangered area stocks, yielded more success.

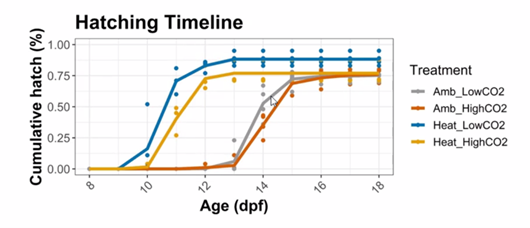

From January to March 2020 (before being rudely interrupted by the pandemic) Chris was able to conduct a multi-stressor experiment on herring embryos in the Shannon Point Marine Center Ocean Acidification facility. Using data from the nearby Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, he modeled the experiment conditions on temperature extremes experienced during the 2014-16 North Pacific marine heatwave, combining this stressor with elevated (2,000 µatm) pCO2 concentrations.

Pacific herring turn out to be dramatically less sensitive to temperature and CO2 stress than Atlantic sand lance, as evident in their respiration, growth rates, and hatching success. Herring held at elevated temperatures did hatch at a smaller size and with fewer remaining yolk reserves, an ecologically significant finding given that smaller larval fish with less endogenous energy often experience lower survival in the wild.

Chris’s fiancé Sarah and their two dogs make their home in Oak Harbor, Whidbey Island, where Sarah works as a veterinarian. Since moving to the northwest they’ve also acquired a cat, Crispy (!), who was a rescue from a serious house fire. This menagerie will soon be moving to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where Chris will be researching Atlantic silverside (Menidia menidia) sensitivity to acidification and hypoxia and elucidating underlying molecular mechanisms of plasticity at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. This is the result of a prestigious National Science Foundation post-doctoral fellowship, which he recently received (congratulations, Chris!).

In the meantime, he is busily riding the ferry in order to study the long-term effects of ocean acidification on the bioenergetics of Pacific herring and their susceptibility to viral pathogens at the USGS Marrowstone Marine Field Station near Port Townsend, while commuting north on Saturdays to do the related analytical chemistry at Shannon Point. And, of course, finding time to hang out with his beloved dogs in his ‘spare time’.

1Murray CS, Wiley D, Baumann H (2019) High sensitivity of a keystone forage fish to elevated CO2 and temperature. Conservation Physiology 7(1): coz084; doi:10.1093/conphys/coz084